Australia’s bushfire disaster occurred under a rise of around 1oC in global average temperatures. The bushfires join, to quote Emeritus Professor Will Steffen, “other recent impacts in Australia including the death of about half of the corals on the Great Barrier Reef from underwater heatwaves; massive floods in Townsville last year, intense drought across the southeast agricultural zone, and the residents of western Sydney sweltering through record-breaking heat”[1]. With Australia’s exposure to such serious climactic and weather events increasingly clear to the community at large, calls to both aggressively curtail emissions and take steps to adapt to changes in our climate, notwithstanding the attention now given to COVID-19, have become urgent. In February APRA announced that they will review the vulnerability of the banking sector to climate related risks with the insights gathered used as the basis to inform an assessment of risks across the Australian economy. Their timetable is aggressive: the design of the assessments will take place over 2020 for deployment in 2021.

As our governments, investors, regulators, businesses and communities enhance their understanding of the physical risks of our changing climate, I discuss the changes that are expected even with less extreme increases in temperature. This understanding is critical for a country such as Australia which already hot and dry.

Australia: the world’s bellwether

The figures associated with the Australia’s bushfire 2019-20 season were startling. More than 10 million hectares across southern Australia were burned, this is greater than the combined area burned in the Black Saturday (2009) and Ash Wednesday (1983) bushfires[2]. The area represents over 20% of Australia’s forests; an unprecedented proportion globally[3]. Further, it has been conservatively estimated that more than 1 billion mammals, birds and reptiles died during the fires[4].

Weather records were broken in the lead up to the fires to create the extreme fire risk. In addition to 2019 being the driest year since records began in 1900, it was also Australia’s warmest year. In 2019 the annual mean temperature was 1.52°C above average[5].

While the bushfires occurred largely in areas that were sparsely populated, Moody's Investors Service gave the following assessment at the height of Australia’s bushfire crisis, “Australia's (AAA stable) general and state governments can absorb the near-term credit impact from the ongoing bushfires, supported by their ample fiscal buffers. However, over time, increasingly frequent and severe natural disasters related to climate change are likely to result in rising and recurring costs that will test the government's capacity to mitigate these costs.”[6]

While Australia is already a hot, dry country, the bushfire disaster drew attention to the profound physical risks faced not only by Australia but also by nations around the world.

What the science tells us

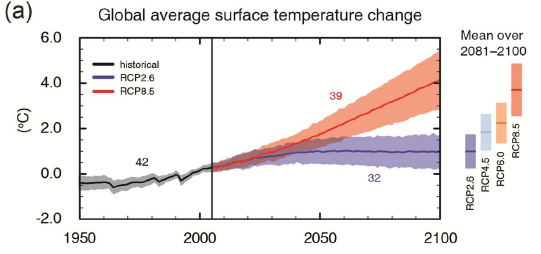

Back in 2013 the IPCC demonstrated that a global temperature increase of well more than 1oC by 2040 is already locked in. In the figure below, the blue line represents the relative concentration pathway (RCP) of CO2 in the atmosphere that represents global warming of between 0.3 and 1.7 degrees by 2100. The red line is the RCP related to warming of between 3oC and 4oC by 2100. Given that our current trajectory already exceeds RCP 2.6 we know that we have already locked in this amount of warming (between 0.3 and 1.7 degrees by 2100).

Figure 1: Global warming by 2100: 0.3oC - 1.7oC for low emissions scenario as determined by the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (RCP2.6), and a temperature increase of 2.6 - 4.8oC for high emissions (RCP8.5)[7]

In the IPCC Special Report[8], we learned how different our world will be to live in at 2oC of warming relative to 1.5oC of warming. We learned that:

- At 1.5oC of warming we will have lost 70% of global tropical coral reefs, at 2oC of warming we have lost them all

- At 1.5oC of warming the Arctic Ocean is ice-free one year out of 100, at 2oC degrees of warming the Arctic Ocean is ice-free one year in ten.

But what else do those two themes tell us? For me the reality of a 2oC world is too extreme to even imagine. If the Arctic Ocean is ice-free what does this mean for sea level rise? For island nations? For rainfall in Australia? How much worse could bushfires become in Australia and across the world? With the IPCC’s Special Report, we came to understand that that there is a profound difference in the lived experience between a world where global warming is limited to 1.5oC and one where the world is allowed to warm to 2oC above pre-industrial levels.

Warming of three or four degrees is almost unthinkable. This means that we need to act on emissions, and we need to act quickly.

It’s also important to understand the rate of change

The climate is a very slow response system. For example, the ice caps take a long time to melt, and while they are melting their temperature does not rise. Ice melts at zero degrees, and the water it sits in stays at zero degrees until all the ice has melted. The whole time it is melting it is consuming energy to address the latent heat required to break the bonds when solids become liquids. This all means that while the ice is melting it is limiting temperature increase as it is consuming so much energy in thawing. When the ice is melted the temperature increase could start to run away.

In addition, oceans take a long time to heat up, and they take as long to cool.

The driving forces of our climate are slow, but inexorable. We need to arrest the cause of any change now to have a chance of limiting warming in 2030 or 2040. Leaving action till 2030 is too late to effect any change.

And yes, I am talking in broad numbers and long timeframes because those are the facts that we have right now. The reality is that taking decisions is not trivial, but we have to remind ourselves that action now is better than action next year and not be paralysed by the enormity of the challenge. The changes we make now will have exponential benefits for our climate later. Reducing the emissions from a process plant by one tonne of CO2 this year can be a lot of work; but it’s better than waiting for 10 years and having to remove more than 10 tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere (given that CO2 accumulates in the environment and we are concerned about absolute concentrations).

Remember that CO2 emissions are cumulative, they last for at least 100 years in the natural environment. When reviewing carbon emissions, it’s often better to think of a budget than of a limit. We are spending our available carbon budget very quickly – we need to limit emissions now so that we reduce the amount of effort this will take later.

The two, urgent imperatives: adapt to a warmer climate and reduce emissions

The reality of Figure 1 is that we have locked in more than 1.5 degrees of warming already. This means that there will be more bushfires. Rainfall will change, there will be more +40 oC days, run-off patterns will change, there will be more droughts and more flooding. We need to prepare for this changed environment and we need to adapt to both live and to do business within it.

Businesses and governments that move early will have an advantage. We are beyond the point where any decision maker will be able to claim ignorance of what lies ahead. Temperatures will rise, the climate will change, and this will have impacts on our physical world. However, we can plan for this. The need for companies to change how they think about themselves and how they do business is clear. The changes will be significant, and with changes of this magnitude comes great opportunity. Fortune favours the brave, and in this new, warmer world, the brave will thrive.

References

[1] The Conversation | I hate to say I told you so but Australia you were warned

[2] CSIRO | The 2019-20 bushfires: a CSIRO explainer

[3] The Guardian | Unprecedented' globally: more than 20% of Australia's forests burnt in bushfires

[4] The University of Sydney | More than one billion animals killed in Australian bushfires

[5] Bureau of Meteorology Annual Climate Statement 2019; CSIRO-BoM 2018 State of the Climate report

[6] Moody’s Investor Services | Research Announcement: Moody's - Credit impact from Australian bushfires for government remains manageable, but recurring fiscal costs set to rise