In this blog, I provide updates from domestic and global forums that are promoting discussion and seeking to find pathways to ensure that the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic is one that features climate action and resilience as a core strategy.

2021

Last week I read the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero 2050 study and attended a webinar delivered by Princeton’s Andlinger Center, which explained the Net Zero America project. I was struck more by the artifacts of the analyses, than necessarily by the numbers each scenario delivered. But more of that later.

What do the scenarios include?

The IEA scenario Net Zero 2050 focuses on delivering a net zero energy system by 2050, paying attention to universal energy access, ensuring energy remains affordable, and enabling robust economic growth. The focus is on a cost effective and economically productive pathway. It requires immediate and concerted action to deliver renewables, electrification of transport and energy efficiency. Emissions reductions required by 2030 will result from technologies which are already available at commercial scale. Innovation is required to deliver the around half of the reductions required between 2030 and 2050. This innovation imperative is immediate. Hydrogen fills the gap where electricity cannot readily displace fossil fuels, or where bioenergy is not sustainable or reliable. It has a fair role to play before 2030.

The Princeton Net Zero America study was technology and policy agnostic and rather plotted the lowest cost trajectory to deliver net zero under a number of scenarios:

- E+: high electrification, no land use change for biomass

- E-: less rapid electrification, no land use change for biomass

- E- B+: less rapid electrification, biomass requires conversion of agricultural land from food to energy crops

- E+ RE-: rapid electrification, renewable energy installations constrained to historical maxima

- E+ RE+: full electrification by 2050, no fossil fuels by 2050, no land use change for bioenergy, no nuclear, no CCUS.

A uniform approach to identifying technologies to be deployed in these studies was used. The technology classes were:

- End use energy productivity including energy efficiency and electrification

- Clean electricity which included firming and network considerations

- Bioenergy and other zero carbon fuels including hydrogen

- Carbon capture, transport, usage and storage

- Reduced non-CO2 emissions

- Nature based solutions.

It’s all about the numbers

The Net Zero 2050 study says $4 trillion needs to be spent on the transition by 2030. This will create millions of new jobs and will improve health significantly. Sale of internal combustion engine cars needs to cease by 2035 and unabated coal and oil power plants must be phased out by 2040. Electricity generation must reach net zero by 2040 and be delivering around half of total end use consumption at that point. There will be significant requirements for flexibility in the electricity system which will be underpinned by, among other technologies, hydrogen and batteries. By 2045 new technologies will be widespread.

We need to deliver energy efficiency savings at three times the average of the last two decades over the next ten years. Electrification of industrial plant and transport becomes more significant as electricity systems tend to net zero. Bioenergy is more significant between 2030 and 2050 and is responsible for the improvements delivered through clean cooking technologies. In 2050, 90% of electricity comes from renewables.

Carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) plays a number of roles:

- It captures emissions from existing energy assets

- It captures emissions from bio energy systems

- It provides a solution for some of the hard to abate sectors (eg., steel and cement production)

- It supports the scaling of hydrogen production

- It enables us to remove CO2 from the atmosphere when we overshoot our preferred concentration.

Behavioural change delivers 4% of the total emissions reductions required to deliver net zero in 2050.

What else do the scenarios tell us?

The IEA Net Zero 2050 scenario highlights yet again that the next decade has to be one of concerted action. The 2020s has to be the decade of clean energy expansion, and focused innovation. The transition is all about people, what they buy and how they live. The IEA clearly states that there is no need for investment in new fossil fuel supply in their net zero pathway. Energy security challenges remain, and will change in nature but will not be eliminated. There will be potential jobs growth but this will not necessarily be evenly spread globally.

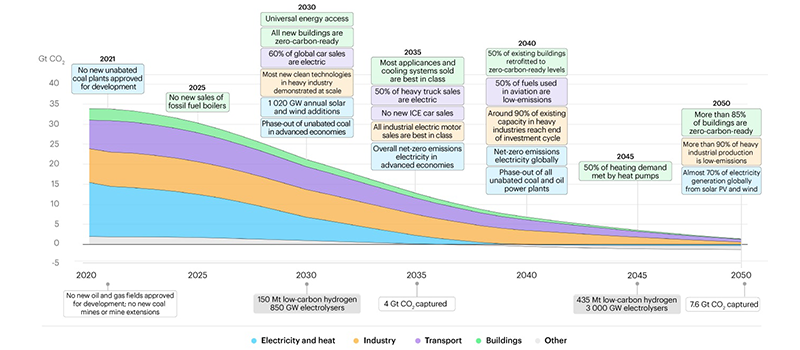

The figure below illustrates seminal aspects of the IEA trajectory.

Figure 1: International Energy Agency Net Zero by 2050

The Net Zero America results were less specific about end points and changes as they were contrasting scenarios. However, by 2050 a number of results are delivered, these are summarised below. In common with the IEA results these include:

- Increase in EVs sooner rather than later

- A requirement for energy efficiency to play a role in delivering net zero

- Nuclear as an energy source is very limited

- Flexibility in systems and resources is a prerequisite

- Biomass and hydrogen have a role to play

- Health benefits through reduced pollution should not be under-estimated

- CCUS presents as a significant part of the technology solution in all scenarios where it was part of the technology mix.

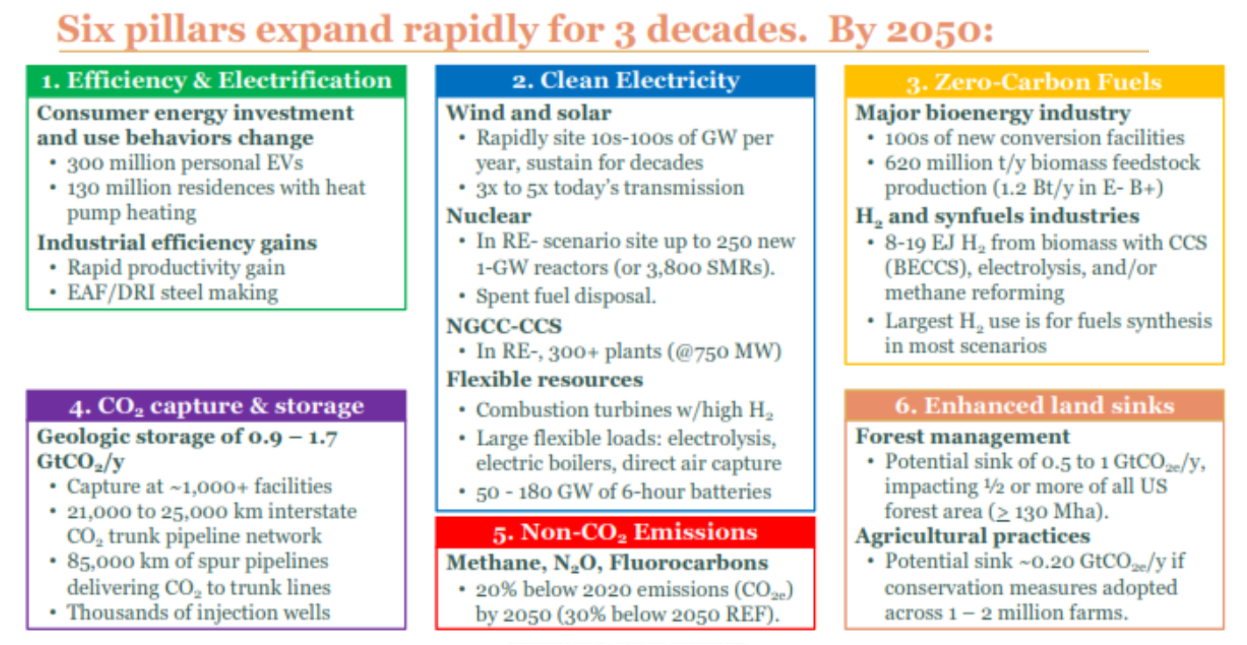

Figure 2: Net Zero America Potential Pathways, Infrastructure, and Impacts

What do we learn from these studies?

- We need to act now and we need to act fast, the decade to 2030 is pivotal, this applies both to implementing technology, which is currently available, and to accelerating the innovation we need to deliver reductions post-2035

- Technology and infrastructure need to be deployed at an unprecedented rate in the next ten years, and we need to invest in enabling technologies now, to support the innovation that we need later (eg. support for a hydrogen economy and EV charging)

- Electrification between now and 2035 will be rapid and underpinned by behavioural change of consumers in many cases

- Electrical network flexibility and stability are a concern to all players

- In the long term we will see industrial transformation in hard to abate sectors

- Least cost scenarios require CCUS to work at scale

- Significant capital will be released, and many jobs will be created, this is much more an opportunity for companies and economies than a threat.

The clear message from both these studies is that we need to act concertedly and quickly. There are significant gains to be had from developing and delivering net zero pathways, and that fortune is likely to favour the brave.

In January the Global Risks Report 2021 was tabled at the meeting of the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos. A major part of this report is the Global Risks Perception Survey. It was surprising that the results of this survey, which played out against the worst of the pandemic, indicated that the risk of greatest concern (albeit marginally) was Climate Action Failure. Globally, the 650 members of the WEF were more concerned about the impact that inaction by governments as regards climate change will have on the global economy, than all the other risks surveyed.

Fast forward four months and two surveys were published in Australia in quick succession:

- The Australian Financial Review published the results of a survey of their readers: AFR readers push Morrison to commit to net zero target, AFR, 3 May 2021

- The Australian Institute of Company Directors published their Director Sentiment Index (DSI) survey of their members: Director Sentiment Index: research findings first half 2021.

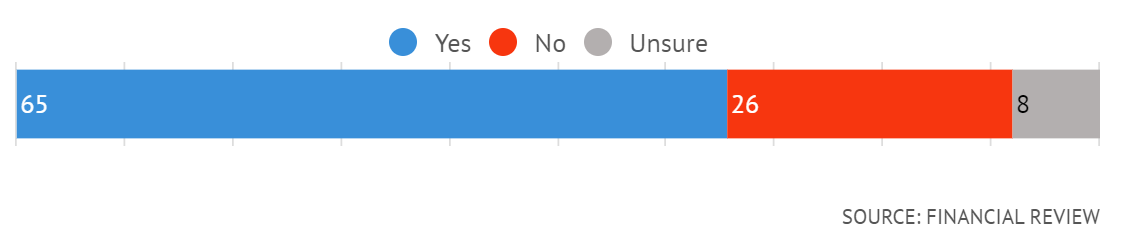

More than 500 AFR readers responded to the readers survey. 65% of readers believe that that Federal government should set a net zero target for 2050 while 26% said this was not necessary.

Figure 1: Australian Financial Review | Should the Federal government set a net zero target for 2050?

The article reporting these results cited respondents as saying that climate change was “not only the biggest challenge facing our country but also the biggest opportunity”. Concerns were voiced that the current inaction on the part of the federal government could lead to Australian businesses missing out on the opportunity that is inherent in the global shift to a zero emissions economy. Respondents also expressed concerns about the potential impact of proposed border adjustment taxes being investigated by the EU and the US and what this could mean for the value of Australian exports.

The AICD survey was run over the first fortnight of April, 1,589 members of the AICD responded in this time. While the most notable response in the survey was the change in director sentiment for the better. The difference in sentiment since September 2020 was a change of 45 points to the positive which is the largest jump ever recorded in the Index.

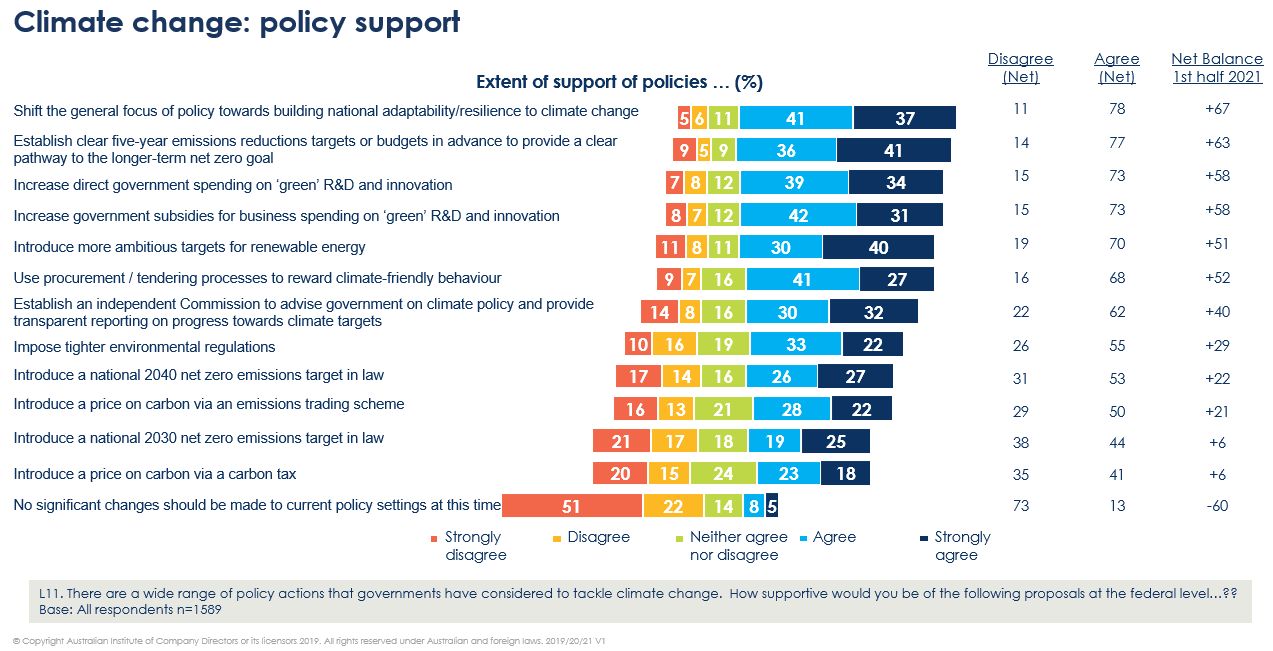

Climate change grabbed almost all of the remaining headlines:

- Directors nominated climate change as the number one priority Federal Government should address in both the short and long-term. In the short term energy policy ranked a near second, in the long term climate change was seen as a clear priority

- Directors viewed the response to climate change of business and community organisations as stronger than that of State and Federal Governments

- 77 per cent of respondents were in support of establishing clear five-year emissions reductions targets to provide a clear pathway to the longer-term net zero goal

- More than half of respondents consider climate change a material risk to their organization, with only 26% disagreeing or strongly disagreeing with this statement

- Renewable energy resources were rated the number one area in importance for infrastructure investment.

While COVID-19 impact and global economic uncertainty were still seen as the most significant economic challenges, their importance had reduced significantly, while climate change was ranked third and its importance had grown significantly.

The significance of climate change to in the survey responses drove the AICD Managing Director and CEO, Mr Angus Armour, to comment, “Directors clearly perceive that climate change risk is not a niche issue only relevant to some sectors, with the challenge now a mainstream item on boardroom agendas.”

Questions were asked specifically about policy support to address climate change, the results of which are included below. These results demonstrate there are real concerns in the private sector about the need to build a national adaptation response. There is a clear appetite start to channel monies into innovation, and a requirement for targets to remove uncertainty and help clear the path to a carbon reduced future.

In summary, the private sector can see the writing on the wall, they recognize that we need real action now and they are calling on the federal government to set meaningful targets and then to step back and let the private sector innovate their way out of the problem.

2020

I recently attended a webinar held by the Coalition for Conservation at which former UK Prime Minister Theresa May and NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian discussed the UK's focus on climate policy, NSW's decarbonisation plan – their Net Zero plan, opportunities for a low carbon economic recovery post COVID and the importance of female leadership on the environment. The promotional material stated, “Leaders like Theresa and Gladys demonstrate why conservative and centre-right governments can act on clean energy and climate policy more effectively than those on the Left, focussing on real outcomes that are environmentally and economically sustainable.” Notable comments included Premier Berejiklian saying, “You don’t need to do much to get to net zero by 2050, it is not that hard to get there”. She also said that May’s centre right government focussed on emissions reduction, assessing climate change as part of economic growth and that the COVID pandemic has humanised us and focussed our attention on our place on the planet.

The recording can be watched on YouTube and coverage of the conversation can be found in The AFR, The Guardian and The Sydney Morning Herald.

I joined a session run by the NSW Department of Primary Industries and Energy which was focussed on the land and primary industries aspects in NSW’s Net Zero plan. The plan has an interim goal of 35% emissions reduction by 2030 and includes a clean energy transition and innovation aspirations, as well as seeking to leverage global investment. The definition of ‘Net Zero’ includes ability to offset.

Points discussed:

- There are opportunities for primary industries in emissions reductions, electrification, energy efficiency, renewable energy zones, productivity and abatement. The Government also recognises that innovation is required in clean technologies and hydrogen.

- In agriculture, productivity gains should be co-benefits in abatement projects and the Government is looking to underwrite the risks in new technologies. The Government also sees carbon markets as a mechanism for climate resilience in agriculture through a number of routes including income diversification.

- Nationwide the land sector delivers the majority of offsets. ERF is providing opportunities for land sector but interest in these has waned recently.

- In NSW, agricultural emissions are dominated by enteric methane.

- Soil carbon is increasingly of interest, it can boost on farm productivity, and is potentially the largest offset opportunity. However, it is difficult to measure and manage. There is also opportunity in vegetation based methods (environmental plantings), but uptake has been low because of transactions costs and scaling issues.

- Income diversification is important for Indigenous owners, and crown lands as well as farmers. Co-benefits are project specific. Under the plan, the NSW Government is looking to help farmers and other landowners value co-benefits to drive uptake of high value projects.

- The Government will explore how carbon projects can work with other government objectives to value co-benefits, however I am not sure whether we will get something like the Queensland Land Restoration Fund. Under the plan, work will be done to remove barriers to access carbon markets and aggregate smaller opportunities.

I was delighted to be invited to present to an international audience on the role of chemical engineers in developing solutions to climate change, and the future role of engineers in industries profoundly affected by the need to act on climate issues. In my presentation I talked about the work Energetics does, the context provided by the Paris Agreement, the problems we have struck as a result of waxing and waning energy and climate policies in Australia, and the solutions. I particularly considered how chemical engineering has helped me to answer some really challenging issues.

I would be happy to make the presentation available upon request. Please feel free to contact me.

2020 was due to be a landmark year for those pushing for a Net Zero future, with world leaders being tasked to update and upgrade their pledges on tackling climate change and emissions targets through to 2030, in other words, countries are required to review and update their Nationally Determined Contributions or NDCs. Unfortunately, the COVID 19 pandemic has meant that COP26 has been postponed until 2021, but it’s imperative to action and momentum continues to ensure we put business on a Net Zero pathway.

‘Delivering Net Zero Virtual Week’ provided practical ideas and strategies on how business can put a Net Zero ambition at the heart of their recovery plan. 3,000+ CEOs, CPOs, CSOs and heads of Sustainability, Energy and Investors came together to share their strategies on how they are building momentum ahead of next year’s COP26 meeting.

My main takeaways were:

- What are the key enabling conditions for a company to start its Net Zero journey? a) belief that this is a ‘must do’ process for business survival, with a long term (30 year), multi stakeholder not shareholder mindset, b) internal alignment supported by adequate KPIs, c) start with a coalition of the willing.

- What are the factors in a carbon market to drive Net Zero? Carbon pricing is a very valuable tool although currently ineffective because Article 6 is not agreed; ultimately the price should be between USD70 and USD100 as this would drive innovation.

- In 2015 the Paris Agreement set the framework. In 2018 the IPCC set the targets. Now we need to change the goals. 2050 is the cut-off point but we need to get their as fast as we can. Ambition should be shorter term than 2050.

- Companies with strong ESG performance have demonstrated greater resilience through the COVID 19 crisis.

- Many speakers presented the case that there are no trade-offs in decarbonisation projects, you are not going to sacrifice production for emissions reduction, there is a clear business case for implementation.

- Energy efficiency is the starting point on the hard to abate sectors, it buys us some time as we work to resolve intractable emissions.

Reuters hosts free events such as this one, together with the Ethical Corporation.

The TEC was established to help the parties to the Agreements under the UNFCCC build policy that better supports the use of technology in addressing the impacts of climate change.

I am a business observer to the TEC and at the end of July, three reports were published. These reports are the outputs from three separate working groups of the TEC. Most interesting for the business community is the report from the Implementation working group (of which I am a member). This report focuses on what is required to scale up implementation of climate technologies – in this instance relating to both mitigation of greenhouse gases, and adaptation to the changing climate. The focus is placed on scale up because technologies are currently available at commercial scale to address the majority of emissions reductions required to meet mid-century targets under the Paris Agreement. For implementation we require innovation in business models and finance structures, this is the focus of the report. Case studies demonstrated that including funding organisations in project definition as early as possible was one of the indicators of success.

A short overview of each report is provided below, follow the links to access the full reports.

Enhancing implementation of the results of technical needs assessments

TNAs are mechanisms which support developing countries to identify and implement climate technologies. This report includes case studies and highlights success factors in TNAs.

Innovative approaches to accelerating and scaling up of climate technology implementation for mitigation and adaptation

The Paris Agreement calls for international collaboration on technology development and transfer to support the purpose and goals of the Paris Agreement. This publication explores innovative approaches to stimulating the uptake of existing climate technologies for mitigation and adaptation. Such innovations can be identified in the following areas: how technology options are selected by countries; how stakeholder views and practitioner knowledge, as well as their preferences, are solicited in climate technology planning; what financial innovations exist for enhancing funding of technology projects and programmes; and what are viable ways of enhancing private sector engagement and incubators.

Technologies for minimizing and addressing loss and damage in coastal zones

Co-developed between the TEC and the Warsaw International Mechanism this report highlights the significance of coastal areas as places where people work and live, and the role of coastal areas in economies of countries, particularly developing countries. The policy brief provides information on an array of technologies – hardware, software, and orgware – currently available to assess risks, reduce risks, recover and rehabilitate from the impacts of climate change in coastal zones. It also highlights challenges and opportunities of these technologies where improvements can be made to help countries prepare better to deal with adverse impacts of climate change in coastal zones.

Carbon offset projects are a significant opportunity for Indigenous communities because of the social outcomes that can be achieved. By their nature, land-use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF) projects enhance connection to land and capacity and capability. In this edition of CMI’s ‘Carbon Conversations’, Shiloh Villaflor from the Aboriginal Carbon Foundation in Cairns and Nolan Hunter from the Kimberley Land Council talk about their business models, highlighting the role of indigenous land management, and how carbon farming projects can build on Indigenous land management.

My takeaways include:

- Carbon projects enable continuation of culture and the practice of savannah burning

- Such projects enable people to the stay on country, the social co-benefits of this are priceless

- The funding is untied and empowers the community to take their own decisions on how to spend it

- Offset projects are one of the few ways that local communities can monetise their Indigenous knowledge.

To help celebrate International Women in Engineering Day, 23 June 2020, I participated in a video put together by IChemE. I joined women from around the world who work in very different fields as we answered the question, “How are female chemical engineers helping to shape the world?”.

It's a great little video you can view here, and I was delighted to participate.

Released 22 June, the International Energy Agency’s report includes 10 recommendations which provide a clear roadmap for ramping up ambition and action on energy efficiency in Australia and around the world. You can access the 'Recommendations of the Global Commission' report here.

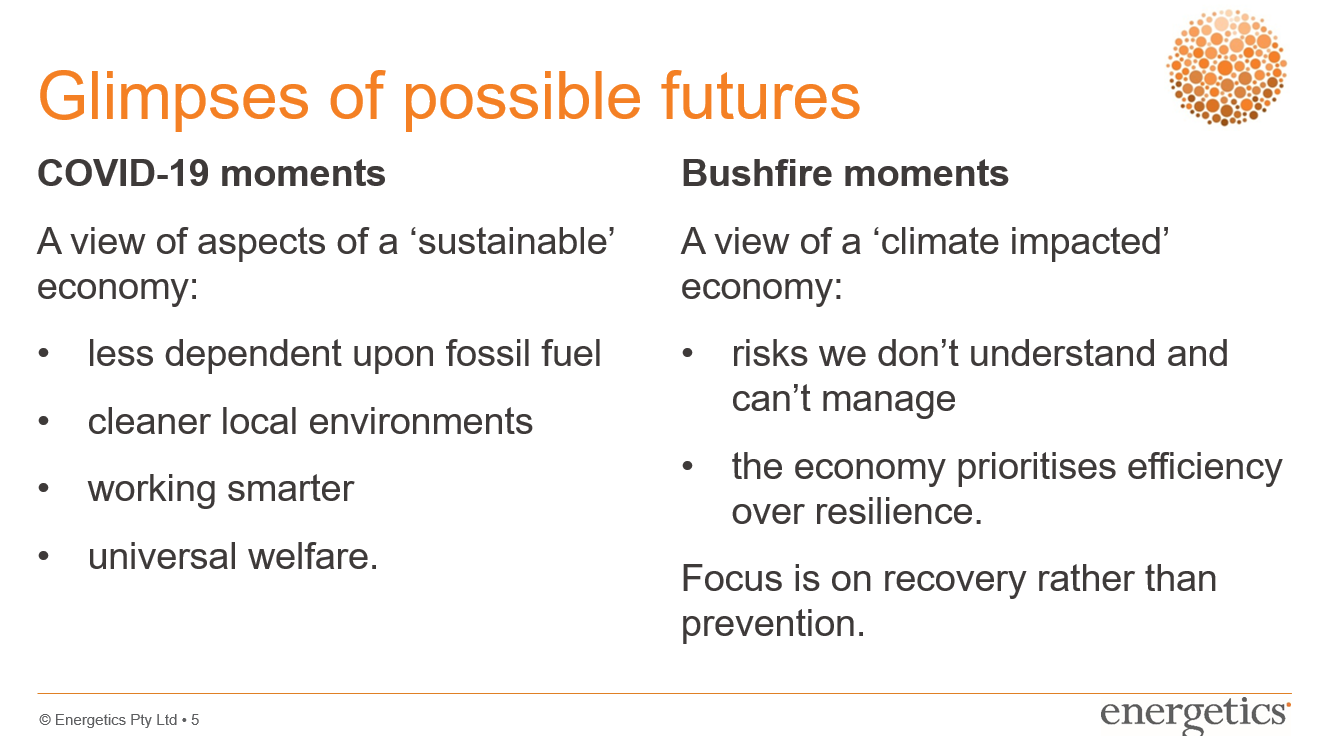

Last week, Energetics’ Associate and climate change physical risk advisor, Dr Nick Wood presented on the topic of “Post COVID19 economic recovery through a climate change lens – the “necessity of necessity”. What future do we want?” I have included a few of his charts below, but the webinar can be accessed here.

The 20th anniversary of the summit, this has been the UN’s largest virtual conference with 15,000 registered delegates. I have attended a number of UN led events recently and the message is consistent: we need urgent, ambitious climate action. Although economic recovery is paramount following the COVID-19 shock, we must not delay and risk losing the fight to limit warming to below 2 degrees. One country provides a great example - Chile. In their updated Nationally Determined Commitment (NDC), they have an absolute carbon budget for 2020 to 2030, a pathway to net zero by 2050 and are anchoring the plan in the SDGs to support a just transition.

Below are some key takeaways from my tweets and from the Summit’s own publicity.

- “You can’t have a successful company in a failed world” – a statement made at the Summit which particularly resonated

- Given the scale of the challenge, we have to rely on private sector funds to help us address the challenges of climate change, governments won’t be able to pay for everything.

- The current crisis is threefold – health, environment and inequality, we need to do better for the less privileged in our country and our region.

- Are we going to see more ambitious NDCs in Glasgow next year? Absolutely!

- (a tweet)

(Richard Yetsenga, Chief Economist/Head of Research of ANZ Banking Group)

- Patricia Espinosa (UNFCCC Executive Secretary) called for inclusive multi lateralism. While some action has been taken on climate it has not been enough to flatten the climate curve. We need urgent action, state and non-state actors must significantly boost their climate ambition.

- Companies need to set more ambitious targets to achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, a United Nations Global Compact report shows. Released to coincide with the start of the Summit., it tracks the progress of corporate sustainability over 20 years. The key findings were:

- Only 39% of companies surveyed believe they have targets that are sufficiently ambitious to meet the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

- Less than a third consider their industry to be moving fast enough to deliver priority SDGs.

- While 84% of companies participating in the UN Global Compact are taking action on SDGs, only 46% are embedding them into their core business and only 37% are designing business models that contribute to the SDGs.

- Many companies focus on Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, Goal 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production, Goal 13: Climate Action, and Goal 3: Good Health and Well-being. Meanwhile, less traction has been made in advancing the socially-focused SDGs such as reduced inequalities, gender equality, and peace, justice and strong institutions.

- 57% of companies measure the impact of their own operations relating to the SDGs but very few extend this to suppliers (13%), raw materials (10%) and into product use (10%)

- Only 29% of companies publicly advocate the importance of action in relation to the SDGs (down from 53% in 2019).

While the UNFCCC secretariat is not holding physical meetings, work continues to progress global climate action. Currently underway until 10 June 2020, is a series of online events which provide an opportunity for stakeholders to share information to maintain the momentum in the UNFCCC process and to showcase how climate action is progressing under the extraordinary conditions created by the global COVID-19 pandemic. At this stage too, it is intended that negotiations and decisions will continue in Bonn in November.

Key points

- 2020 is a critical year as updated Nationally Determined Commitments (NDCs) are due from all signatories to the Paris Agreement. The delay in the timing of the COP does not affect this requirement.

- While the virus has changed the technical nature of how negotiations occur, COVID-19 has shown that governments can make clear and decisive decisions based on scientific information. They in turn need to engage more deeply with the science to guide their climate response, both in terms of emissions reductions but also to adapt and build resilience.

- Six climate positive principles were articulated: the need for green jobs, recovery packages should include Paris climate goals, fossil fuel subsidies need to end, carbon should be priced, climate change needs to be incorporated into government decision taking, no community should be left behind, and countries must recover better together.

- There are elements of a green recovery that can be seen through private sector commitments from groups such as Blackrock, and governance structures through UN agencies.

- Leadership is being shown by the EU through financial support for developing countries to establish a green recovery.

- Lord Stern’s presentation reminded attendees of the warnings he and others issued over a decade ago: we need to take significant action and it needs to start now. He noted that three years of rebuilding activities will be needed in a post-COVID-19 world that must also prepare us for a world increasingly impacted by climate change.

- Central banks move more quickly than finance ministries (a comment made by the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System). There are concerns that ‘brown’ recovery responses will only increase banks’ exposure to climate risks. The network includes 66 central banks. All of the central banks are including clear requirements to account for climate risks.

Attended by 292 participants, the event featured the work of the Technology Executive Committee (TEC) and the Climate Technology Centre & Network (CTCN). Updates were given on the implementation of the technology framework. As a business observer to the TEC, I was both a presenter and a panellist, and I spoke to the issues for the private sector in the deployment of climate technologies and the role of policy.

Key points (raised in my presentation)

- The challenge in setting policy for technology, particularly in the cleantech[1] space, which is innovating and changing daily, is that technology-specific policy will be out of date almost as soon as it is written. It is best to define the outcomes you are looking for, rather than to specify the technologies to be considered or implemented.

- In “Enhancing finance for the research, development and demonstration of climate technologies”, a report produced by the TEC in 2016 , one of the principal messages was that the technology innovation required to deliver the majority of emissions reductions needed by 2040 has already occurred, what we require is innovation in business model and finance structures. However, in the absence of surety, the private sector has not been pursuing these technologies. Policy must be clear about the outcomes required of a system, be this the extent of emissions reductions, a country target within a Nationally Determined Commitment (NDC) or an emissions intensity for a sector. If policy is clear, the private sector will develop the business case to deliver the outcomes sought.

- Innovative local businesses can lead. Governments may need to help in the co-development of new business models, and it may be necessary to explore new sources of finance and innovative finance models.

- A good role for the public sector is to guarantee a market. In Australia there are many renewable power purchase agreements and many of the first PPAs were commissioned by local governments. Similarly, a public body could create a market for LEDs or ensure that electric buses are filled with their employees.

- This is particularly important as countries assess their COVID-19 recovery plans which will in many instances result in significant investment. Being clear about the desired outcomes (emissions reductions, alignment with the goals of the Paris Agreement, adequate consideration of adaptation) and aligning any government funding with these requirements is a prerequisite for “building back better”.

- There are three aspects of the recovery which are important for cleantech:

- Unlike the GFC which had an austerity-led recovery, the COVID-19 recovery is a growth recovery. Companies need to be encouraged to take a growth path

- We need more jobs

- We need to take decisions for the future, not the past, companies should rebuild for what they want to be, not what they are.

- NDCs are essentially development plans, they highlight the big decisions and where big opportunities lie. They should be central to how government funds are invested in the recovery.

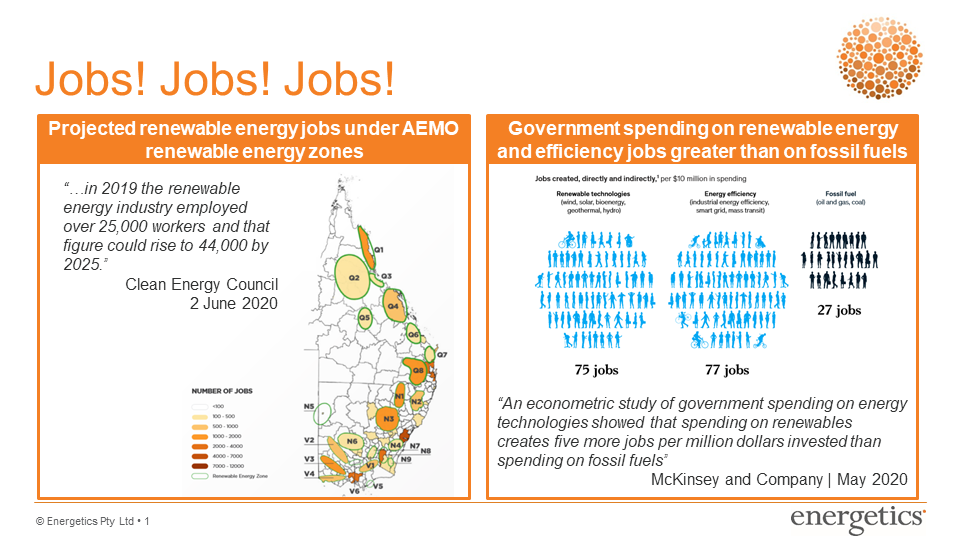

- ‘Green’ economic recovery measures will perform at least as well as those which don’t take the environment into account. The Clean Energy Council report “Clean Energy at Work” published this month[2] highlights the number of jobs which could be created in the renewable energy space, about 20,000 in five years – for scale the coal sector employs around 34,000 people. A week earlier McKinseys published “How a post-pandemic

- stimulus can both create jobs and help the climate” [3], this is based on an assessment of the American economy. The background work showed that at least two if not three jobs could be created for each dollar invested in renewable energy or energy efficiency when compared with the same investment in the fossil fuel sector. The report said you could create up to five time the jobs.

- We need to rebuild for resilience, not just for the next pandemic, but in the context of climate change. We have locked in a temperature increase of at least 1 degree and we have to rebuild in that context. In Australia while there is limited certainty in climate policy, we know what is happening with the weather. Companies who build adaptation into their rebuild efforts will reap the rewards in the long term.

The webcast recording and presentations, can be accessed via the Technology Executive Committee (TEC) and Climate Technology Centre and Network (CTCN) websites.

References

[1] Here ‘cleantech’ refers to technologies that serve both climate change mitigation and adaptation goals.

[2] Clean Energy Council - Clean energy at work study reveals enormous jobs opportunity

[3] McKinsey & Company - How a post-pandemic stimulus can both create jobs and help the climate

This meeting presented a new report, Modernizing governance: engaging with directors on challenges ahead. The discussion centred on the various crises that boards are attempting to navigate: the COVID-19 health crisis, the economic crisis and the climate crisis, highlighting that it is not possible to survive the current challenges without rethinking how decisions are made at a board level. What made this session stand out was that it did not focus on governance structures for managing climate risks, it explained that the world in which we are operating has changed so profoundly that boards need to adjust how they make decisions. This change is driven by increasing uncertainty and risk, not least of which are COVID-19 and the climate crisis, other sources of uncertainty are IoT, Industry 4.0, the changing demographics in the work force, and many others.

The foreword to the report states, “This report represents the first phase of a journey to propose a set of instruments that will help boards manage their fundamental tasks and to fulfill their duties. Built on interviews with board members, it highlights practical changes needed in all areas of board responsibility and showcases useful best practices...Businesses need to go further to protect and renew their company’s social license to operate. It is time for the board to lead the way towards true value creation - dismissing “fake profit” which takes nature and people for granted, remunerating services rendered and repairing damage caused. Sending the bill for our misconduct to the weakest or to the next generation is not acceptable and boards have a duty to change their actions and behaviour accordingly.”

Joint statement from 15 representative organisations

Released on 25 May, was a joint statement by the Australian Conservation Foundation, Australian Council of Social Service, Australian Council of Trade Unions, Australian Energy Council, Australian Industry Group, Brotherhood of St Laurence, Business Council of Australia, Carbon Markets Institute, Energy Efficiency Council, Energy Users’ Association of Australia, Investor Group on Climate Change, Master Electricians Australia, Property Council of Australia, St Vincent de Paul Society and WWF Australia. The statement leads with, “Beyond the pandemic, Australian prosperity also depends on dealing with other long-term challenges – including the transition to net zero emissions. Economic recovery efforts can and should contribute to addressing these long term challenges.” The statement can be read in full via this link.

Thought leadership on the role of business

McKinsey Quarterly issued in May considered the role of business in the recovery and building of resilience, saying, “The COVID-19 pandemic presents an unforeseen challenge to industrial operators as they face the immediate impact of plummeting demand for many products, as well as pressing needs to ensure the safety of employees. Yet even as industries grapple with structural changes, and as societies and economies pivot to the “next normal,” companies themselves have a window of opportunity to adapt their operations to help reduce the disruption that climate change will ultimately bring.” I do recommend this article![1]

Carbon conversations: webinars with the Carbon Markets Institute

On 15 May 2020 I participated in a webinar, “Carbon Conversations” hosted by the Carbon Markets Institute (CMI). Our topic was “Industry trends and market movements in the net-zero business transition”. I was joined by Peter Castellas, CEO of Tasman Environment Markets Australia’s largest carbon offset provider. We covered emissions reduction pathways, zero net portfolios, disclosure and reporting as well as balancing emissions reductions and adaption in the recovery post-COVID. You can access the webinars here. Noting too, a particularly insightful discussion was held with Opposition spokesperson Mark Butler, Shadow Minister for Climate Change and Energy, leader of the Greens, Adam Bandt and Zali Steggall, MP and Federal Member for Warringah. It was reassuring to hear well developed and balanced policy positions which can deliver net zero outcomes for Australia in line with Paris Agreement commitments.

References

[1] ibid