Originally published by 'Energy and Mines'

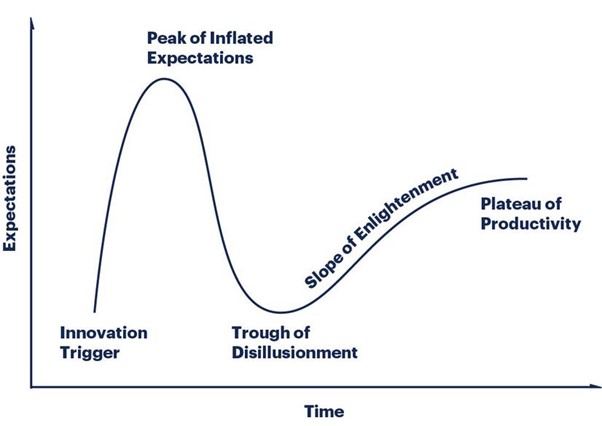

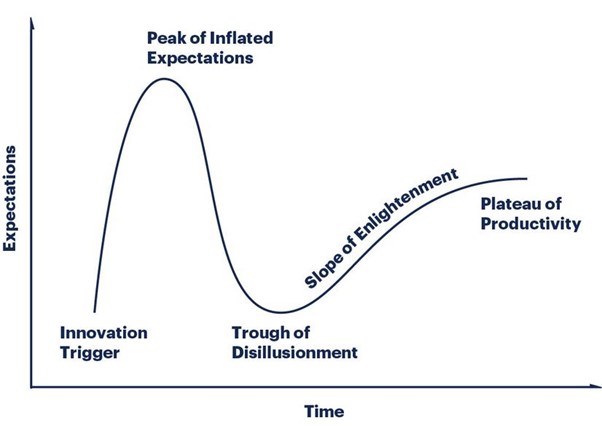

Remember Google Glass? Few gadgets debuted with as much hype as Google Glass, the smart spectacles unveiled in 2012. Although it is still being used in some specialist applications, Google shelved the product in 2015. Gartner, the global research and advisory firm developed the Gartner Hype Cycle to track the maturity and adoption of technologies and applications. Google Glass rapidly passed through the Peak of Inflated Expectations and currently sits in the Trough of Disillusionment. So, where is hydrogen for mining on the Gartner Hype Cycle?

Hydrogen certainly sits well past the Innovation Trigger. After all, routes to make hydrogen and its application in chemical processes and fuel cells have been known for years. Hydrogen powered the first internal combustion engines over 200 years ago.

Figure 1: Gartner hype cycle

Perhaps, it could be approaching the Peak of Inflated Expectations? Despite hydrogen production currently being carbon-intensive either via the preferred route of steam methane reformation or the emerging application of electrolysis of water, it is seen as a key part of the decarbonisation of energy use and of certain chemical and mineral processes. However, for hydrogen to make a significant contribution to clean energy transitions, green hydrogen - hydrogen produced using electrolysis powered by renewable energy, must be used. The production of hydrogen in bulk from renewable energy is neither easy nor is it currently cheap.

Comparing hydrogen with other fuels

What is “cheap” for the mining industry needs to be considered in terms of the fuels that hydrogen competes with. Here we focus on the movement of materials; the “easy” problem to solve. The other source of emissions that hydrogen could decarbonise is associated with mineral processing – high temperature heating and metals reduction. However, the routes to decarbonisation are less well defined for mineral processing than for materials movement.

Diesel is a great fuel. It is energy dense, easy and relatively safe to handle and offers valuable flexibility for mine operators. It would take significant advances in technology for green hydrogen to be cost effective against diesel. That said, a few years ago you could not imagine solar PV offering electricity below the short run marginal cost of electricity sourced from coal, but that milestone has already been achieved.

Diesel, however, carries the burden of greenhouse gas emissions, and its future use is no longer consistent with the aspiration of many miners in Australia and elsewhere to achieve net zero emissions at or before 2050. Examples include BHP, Rio Tinto, FMG and, South32.

Therefore, hydrogen is not competing against diesel but against other options for the movement of materials that result in zero emissions. Fuel use by large mobile mining equipment currently generates 30-50% (and up to 80%) of the scope 1 emissions at a mine. Green hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles would eliminate these emissions. But so too would battery electric vehicles (charged by renewable electricity) with or without trolley assist. It is therefore necessary to compare the potential cost of hydrogen-powered fuel cell electric mining equipment with plug-in battery-electric mining equipment.

There is no question that battery electric vehicles (EVs) have the lead on hydrogen fuel cell EVs for light vehicles, where payload and range are less of an issue. The average Australian car is driven for less than 40 km per day. Not so a mine dump truck, which must operate all day, every day without stopping. Further, every extra kilogram of battery storage is a kilogram of ore that cannot be carried.

Fuel cell electric vehicles, though more expensive to deploy, are better suited to long-haulage transport due to higher range relative to battery electric vehicles, a key consideration for long distance transport. Other benefits of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are the elimination of diesel particulates, less noise, less heat generation and shorter refuelling times.

It is therefore not surprising that the Australian mining industry is looking seriously at hydrogen fuelled vehicles. The leader is probably Fortescue Metals Group (FMG) who is planning to purchase ten hydrogen fuel cell buses, replacing a fleet of diesel buses, at the Christmas Creek mine, and will establish a solar powered plant for hydrogen production at the site. This is part of a $32 million total investment in hydrogen fuelled transport. The buses will be provided by the heavy hydrogen vehicle manufacturer HYZON Motors, and they will be equipped with higher powered fuel cells, generally used in trucks, to allow for like-for-like performance replacement for the previous diesel fleet[1].

*FMG joins BHP, Anglo American and HATCH to form the Green Hydrogen Consortium (GHC)[2]. Aimed at identifying opportunities to develop green hydrogen technologies for resources sectors and other heavy industries, the Consortium seeks to provide a mechanism for suppliers and operators to contribute and engage with development activities.

Alannah MacTiernan, Western Australia’s Minister for Regional Development welcomed this industry collaboration to help decarbonise mining operations and cement WA’s place on the world stage as a green hydrogen innovator and producer. The Minister recently announced $22 million to accelerate renewable hydrogen with nine initiatives including support for the FMG hydrogen-powered bus project[3].

Clean hydrogen is planned for many nations

Japan, the Republic of Korea, China, Germany, Britain, the European Union, United States and New Zealand all have plans for clean hydrogen. In some cases such as California, this extends to specific targets with respects to uptake of fuel cell electric vehicles and development of refuelling infrastructure. Aside from Australia’s National Hydrogen Strategy, around the world there are 19 other hydrogen strategies and roadmaps. There is an expectation that hydrogen has a major role to play in decarbonisation, including within the mining sector. Consensus is that large-scale and rapid deployment of hydrogen technologies will emerge from 2030 onwards.

Which brings us back to the Gartner Hype Cycle. History contains examples of disruptive technologies that will make their mark in 10 years’ time, and the 10 years in question keeps receding. Some technologies to produce zero-emissions hydrogen are well understood (e.g. electrolysers powered by renewable electricity) but are expensive and have not been deployed at scale. Other technologies such as photo-catalysts are still being developed. This is why the recent Technology Investment Roadmap Discussion Paper published by the Australian Government placed hydrogen vehicles at Technology Readiness Level 7 (Demonstration in operational environment) but with a very high cost of emissions abatement at around $1,000/t CO2 abated.

There are many who see green hydrogen as a vital part of Australia’s future energy landscape with exciting potential as a future energy export; and it’s encouraging to see governments and companies take steps to support its development. However, the gap between the current status of hydrogen for materials movement and other applications in mining, and what is required for it to be economic against alternatives provides ample scope for a slide down to the Trough of Disillusionment.

Time will tell whether hydrogen for mining languishes in the Trough of Disillusionment because other zero-emissions technologies prove to be more cost-effective. Or whether it climbs to the Plateau of Productivity as hydrogen becomes the flexible fuel of the future.

References

[1] Fortescue Metals Group | Fortescue advances hydrogen technology at Christmas Creek

[2] Australian Mining | Mining heavyweights form Green Hydrogen Consortium

[3] Government of Western Australia | $22 million investment to accelerate renewable hydrogen future